If 9-year-old Daniel Asia had gotten his way, his music career would have started by learning clarinet. But his two front teeth stuck out too much, so his music teacher at View Ridge Elementary School in Seattle suggested trombone.

Fine, Asia said, trombone it was.

The trombone suited him, Asia learned, and by ninth grade he was playing in bands and chamber ensembles. But around the same time, he needed braces to correct those front teeth, so the trombone had to be set aside.

Asia’s high school music teacher made him an offer: “I’ll play trombone. Why don’t you conduct us?” Asia agreed, and that day he got his first intimate look at a musical score – all thanks to his teeth that, until then, had only held him back, musically speaking.

“It was a strange unfolding,” Asia admitted as he reflected recently on his musical beginnings.

But the moment helped lay the foundation for Asia’s career. He has become an accomplished composer of contemporary classical music that has been performed by professional symphony orchestras and other ensembles across the U.S and the world. He’s now a professor of composition at the Fred Fox School of Music, where he began in 1988 as an associate professor.

‘Pushing the notes around’

Asia’s family has a long history of careers in the same industry – but that industry isn’t music, or even art. Asia’s mother, father and uncle were lawyers. So were his sister and brother-in-law. His son is now continuing the family’s legal lineage.

Still, music wasn’t that odd a career choice. Asia describes his father as a talented pianist who had dreams of becoming a concert pianist one day. But that changed sometime in the late 1920s, Asia said, when his grandfather died and his father was forced to choose a more stable career, thus beginning the family’s line of lawyers.

Asia took two years of music theory classes in high school and in summer programs. Music theory, or the study of music’s theoretical elements – like notation, pitch, harmony and melody – is “a way into composition,” Asia said, “a way of pushing the notes around, to make sense of them.”

When it came time for college, Asia intended to get as far away from Seattle as he could while remaining in the continental U.S. After his music teacher told him about Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts, he applied. He began at Hampshire in 1971.

But studying music wasn’t the plan, Asia said.

“I thought, ‘Here I am at this liberal arts institution. Maybe I should try and branch out and study other things and see what’s going on,'” he said. That lasted for about three weeks before he returned to music. “I couldn’t live without it. I didn’t know if I was going to be a good composer, but I wanted to see if I could be.”

Asia was allowed into Hampshire’s music program midsemester, and once again, composing consumed him. During his sophomore year, he wrote “Sounds Shapes,” a three-movement choral piece that was recorded in 2010 by the BBC Singers, the broadcasting corporation’s professional chamber choir.

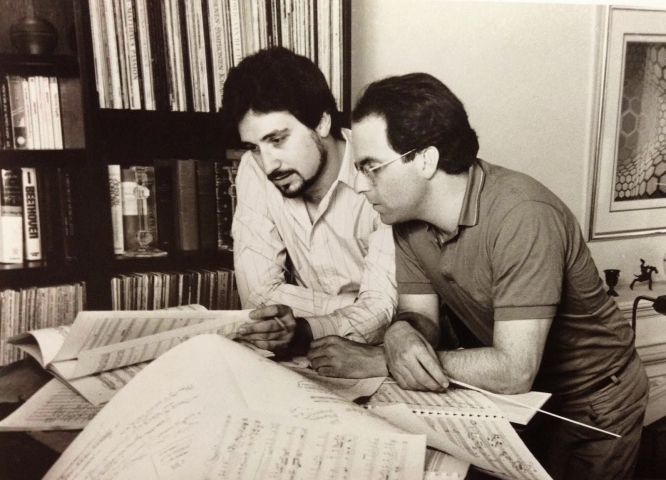

Asia graduated from Hampshire with a bachelor’s degree in 1975 and went to the Yale School of Music, where he studied composition and conducting full time under Jacob Druckman, a renowned composer and chair of the school’s composition department. Druckman died in 1996.

Asia learned little from his professors, he said – “composers learn by doing” – but one piece of Druckman’s advice stood out.

“One of the most important things Jacob told me was when you’re listening to a piece, and you hear something that makes your jaw drop, go back and see what it was,” Asia says. “I did that for a long time and I still do it.”

During his time at Yale, Asia wrote his first string quartet and Piano Set I, his first major composition for that instrument, among other pieces. He earned his master’s degree in 1977.

Becoming a composer

Asia’s newly acquired advanced degree from an Ivy League school might have spoken to his potential talent as a composer, but it didn’t hold the answers for how to become one.

“I didn’t know how to make a living as a composer. I came from this family of lawyers,” he said.

So, he moved to New York. Soon after he arrived, Asia made a bold attempt to get a conducting job with the American Composers Orchestra, but wasn’t hired. Instead, he went on to start his own ensemble, Musical Elements, with fellow composers and Yale graduates Clinton Everett and James McElwaine. Asia served as musical co-director of the ensemble alongside Robert Beaser.

The group quickly made a name for itself, presenting programs of works written by its members but also other composers. Musical Elements, Asia said, gave the first New York performances of pieces by György Ligeti, Yehudi Wyner and Luciano Berio, all of whom went on to become renowned composers.

Blake Cesarz, a UA doctoral student in musicology, studied the history of Musical Elements and the ensemble’s impact on the classical music scene in New York City for his master’s thesis. Cesarz said he found that the ensemble helped bridge the gap between composers and musicians in uptown and downtown Manhattan, which were then two historically separate camps.

“Performing good, interesting music from these broadly defined camps to make entertaining, artful programs that wouldn’t alienate an audience was the core idea,” Cesarz said.

By the fall of 1979, Asia was helping manage Musical Elements programs from what was then West Berlin, where he was composing music on Germany’s equivalent of a Fulbright Scholarship.

In the fall of 1980, he began as an assistant professor at the Oberlin Conservatory in Ohio, where he also served as conductor of its wind and contemporary ensembles. Asia continued to compose music during that time, but he also expanded on his work from years ago.

Asia left Oberlin in 1986 and went to London on a Guggenheim Fellowship and a Fulbright Arts Award. While there, he wrote, among other works, his first symphony. That piece was recorded by the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra in the 1990s under the direction of James Sedares, an accomplished conductor and composer.

After joining the UA faculty as an associate professor in 1988, Asia served as the composer-in-residence for the Phoenix Symphony Orchestra from 1991 to 1994. The orchestra recorded Asia’s second and third symphonies, also under the direction of Sedares.

The scholarship of composition

Asia said he doesn’t know how many compositions he has amassed since he began writing music. Some composers count their works and some don’t, he said. He estimates his catalog amounts to between 60 and 100 pieces.

That output, Asia said, is the best indicator of how he conveys his scholarship to the world. The impact of that scholarship, he added, is measured by the emotional response his music stirs in his listeners.

“We composers and musicians are interested in having our listeners experience things that are not mediated through words but mediated through sound – sound that has meaning to the people who hear it,” he said. “That’s the hope, anyway.”

Asia notes that there’s a section of faculty in his own school whose work is primarily scholarship – musicologists and historians who spend much of their time analyzing compositions to bring “a new understanding of things that already exist.”

Cesarz, as a musicologist who has analyzed a selection of Asia’s scholarly output, said that work has helped Cesarz focus his own scholarship. Before he started researching Musical Elements, Cesarz said, he didn’t have a clear idea of where his career as a musicologist might lead. Now he is interested in researching recent American classical music more broadly to discover how other groups had similar influences much like Musical Elements had in New York.

Asia, Cesarz said, proved to be a challenging colleague with strongly held views, but was always willing to help others gain a stronger understanding of the impact music can have.

“There’s sort of a religiosity to his viewpoints,” Cesarz said. “But the way he goes about it challenges people to rise to the occasion.”

Asia’s strong viewpoints extend to his own work, evidenced by one of his rules as a composer.

“I always tell composers, ‘Don’t let anything out of your studio unless you really love it,'” he said. “You have to love your piece almost the way you love a child.”